What is EBIOS RM?

EBIOS Risk Manager (EBIOS RM) is the method published by the French National Cybersecurity Agency(ANSSI – “Agence nationale de la sécurité des systèmes d’information”) for assessing and managing digital risks(EBIOS: “Expression des Besoins et Identification des Objectifs de Sécurité” can be translated as “Description of Requirements and Identification of Security Objectives”) developed and promoted with the support of Club EBIOS (a French non-profit organization that focuses on risk management, drives the evolution of the method and proposes on its website a number of helpful resources for implementing it – some of them in English).

EBIOS RM defines a set of tools that can be adapted, selected and used depending to the objective of the project, and is compatible with the reference standards in effect, in terms of risk management (ISO 31000:2018) as well as in terms of cybersecurity (ISO/IEC 27000).

Why is it important?

Why use a formal method for your (cyber)security risk analysis and not just slap the usual cybersecurity technical solutions (LB + WAF + …) on your service?

On a (semi)philosophical note – because the first step to improvement is to start from a known best practice and then define and evolve your own specific process.

Beyond the (semi)philosophical reasons are then the very concrete regulations and certifications you may need to implement right now, and the knowledge that in the future the CRA regulation will require cybersecurity risk analysis (and proof of) for all digital products and services offered on EU market.

OK, so it is important: lets go to the next step:

How is it used?

First a few concepts

In general the target of any risk management /cybersecurity framework is to guide the organization’s decisions and actions in order to best defend/prepare itself.

While risk/failure analysis is something we all do natively, any formal practice needs to start by defining the base concepts: risk, severity, likelihood, etc.

Risk and its sources:

ISC2 – CISSP provides these definitions:

- Risk is the possibility or likelihood that a threat will exploit a vulnerability to cause harm to an asset and the severity of damage that could result

- a threat is a potential occurrence that may cause an undesirable or unwanted outcome for an organization or for an asset.

- asset is anything used in a business process or task

One of the first formal methods to deal with risk was FMEA: Failure Modes, Effects and criticality Analysis that started to be used/defined in the 1940s (1950s?) in US (see wikiipedia). This is one of the first places where the use of broad severity(not relevant/ very minor/ minor/ critical/ catastrophic) and likelihood(extremely unlikely/ remote/ occasional/ reasonably possible/ frequent) categories have been defined.

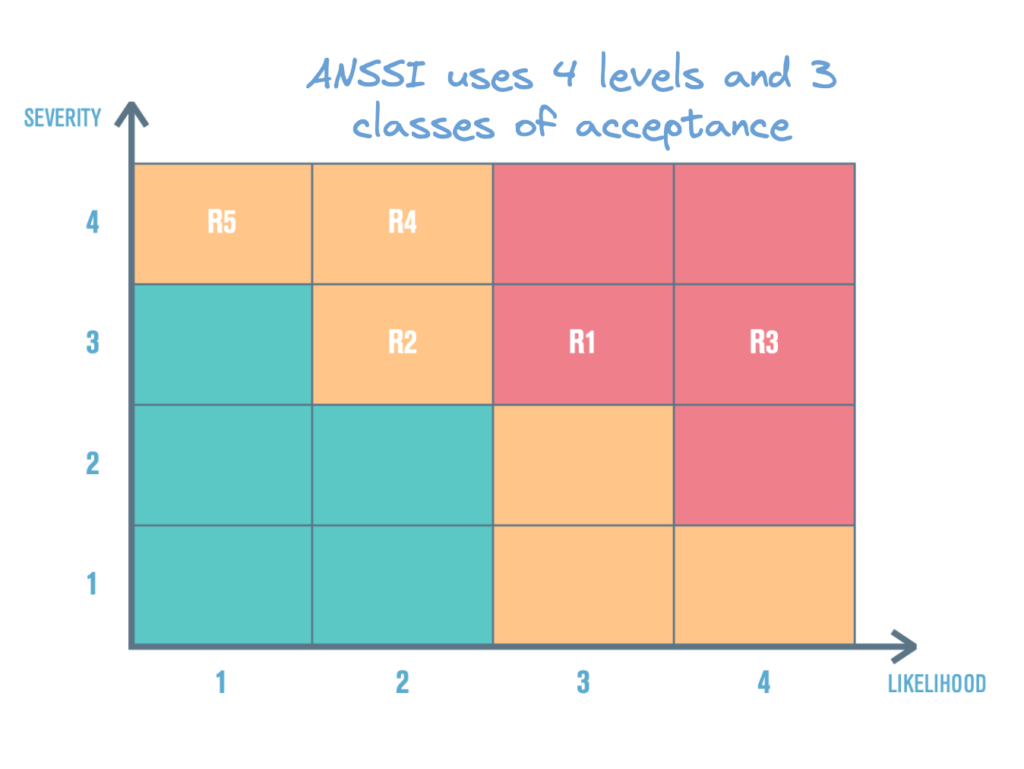

ANSSI defines 4 levels of severity in EBIOS RM:

G4 – CRITICAL – Incapacity for the company to ensure all or a portion of its activity, with possible serious impacts on the safety of persons and assets. The company will most likely not overcome the situation (its survival is threatened).

G3 – SERIOUS – High degradation in the performance of the activity, with possible significant impacts on the safety of persons and assets. The company will overcome the situation with serious difficulties (operation in a highly degraded mode).

G2 – SIGNIFICANT – Degradation in the performance of the activity with no im- pact on the safety of persons and assets. The company will overcome the situation despite a few difficulties (operation in degraded mode).

G1 – MINOR – No impact on operations or the performance of the activity or on the safety of

persons and assets. The company will overcome the situation without too many difficulties (margins will be consumed).

ANSSI defines 4 levels of likelihood:

V4 – Nearly certain – The risk origin will certainly reach its target objective by one of the considered methods of attack. The likelihood of the scenario is very high.

V3 – Very likely – The risk origin will probably reach its target objective by one of the considered methods of attack. The likelihood of the scenario is high.

V2 – Likely – The risk origin could reach its target objective by one of the consi- dered methods of attack. The likelihood of the scenario is significant.

V1 – Rather unlikely. The risk origin has little chance of reaching its objective by one of the considered methods of attack. The likelihood of the scenario is low.

ANSSI defines some additional concepts:

Risk Origins (RO – this is similar to Threat Agent/Actor in ISC2 terminology) – something that potentially could exploit one ore more vulnerabilities.

Feared Events (FE – this is equivalent to Threats in ISC2 terminology)

Target Objectives(TO): the end results sought over by a Threat Agent/Actor

A side note : quantitative analysis

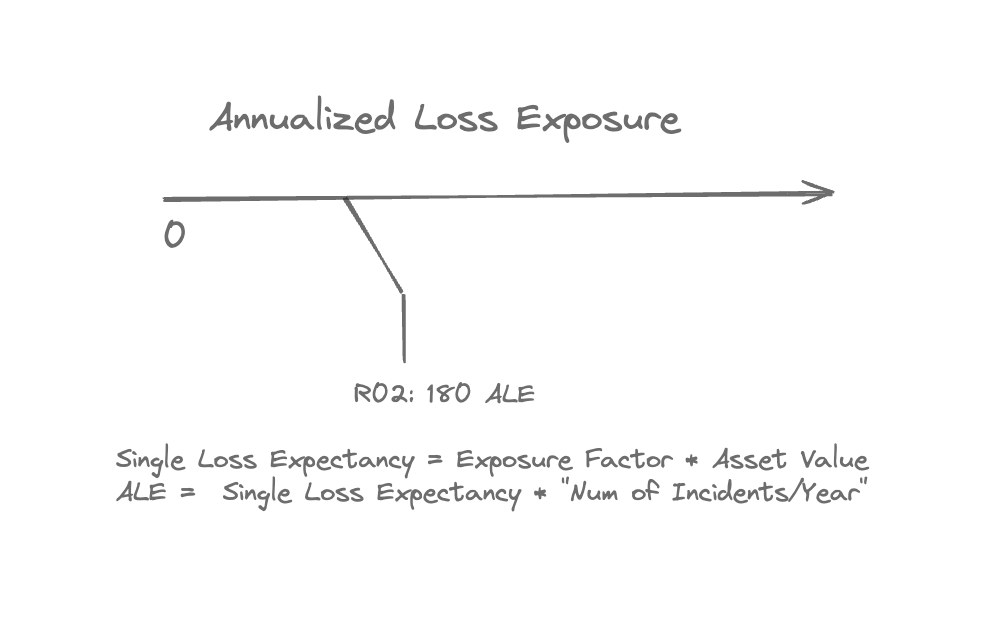

ISC2 – CISSP recommends using quantitative analysis for risk qualification:

Getting there requires to qualify your asset value or at least how much a risk realisation would cost you (Single Loss Expectancy) and then compute an annual loss so that you can compare rare events but costly with smaller but more frequent.

I think the two methods are compatible as nothing stops you to define afterwards some thresholds that map the value numbers to a severity class (eventually depending not only on the ALE but also on your budget/risk appetite/risk aversion)

A process of discovery

The risk management methods are at their core similar and all contain a number of steps that help establish: what is that you need to protect, what could happen to it, and what could be done to make sure the effects of what ever happen are managed (or at least accepted).

So the steps are in general (with some variance on the order and emphasis) :

- identify assets (data, processes, physical)

- identify vulnerabilities associated to your assets

- identify the threats that exist in your operative environment (taking into account your security baseline)

- identify the risks and prioritise action related to them based on their likelihood and severity

..cleanse and repeat.

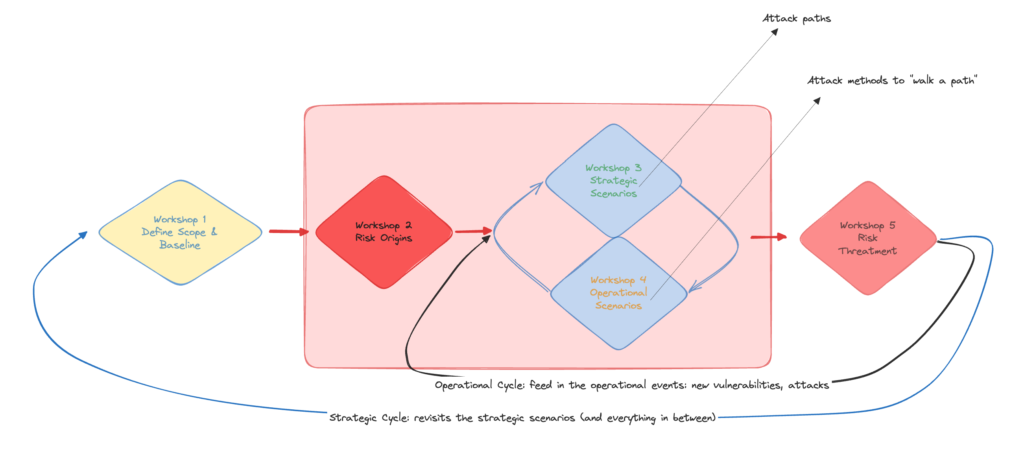

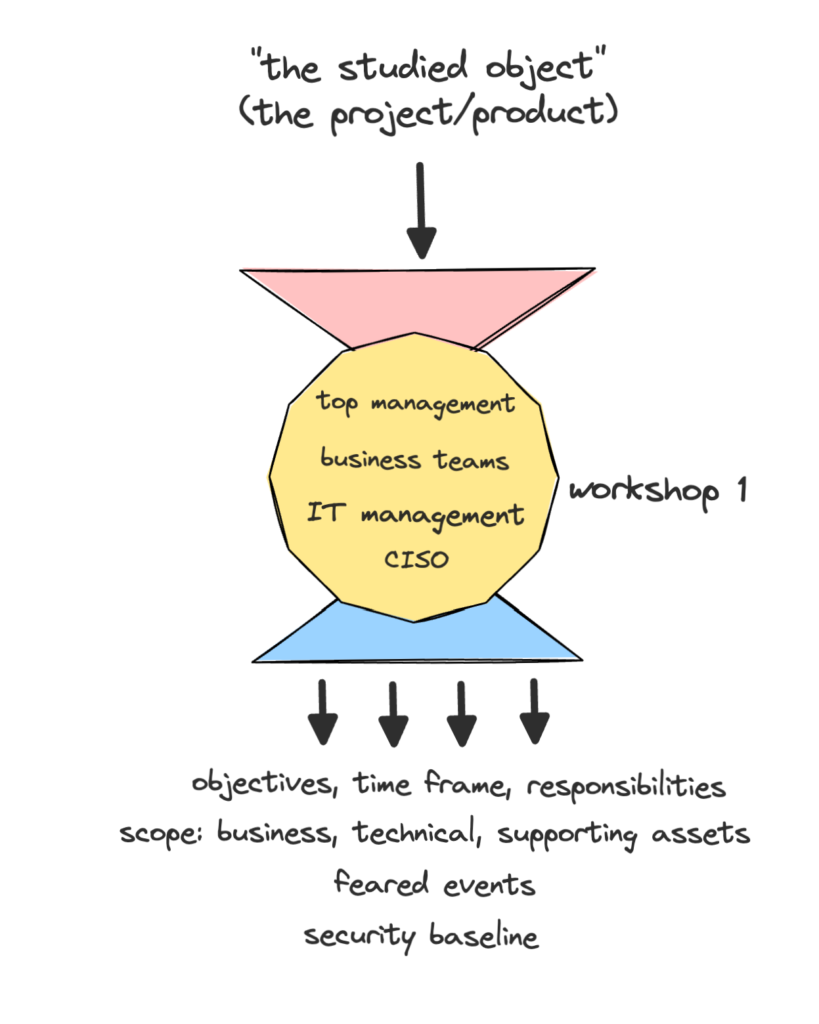

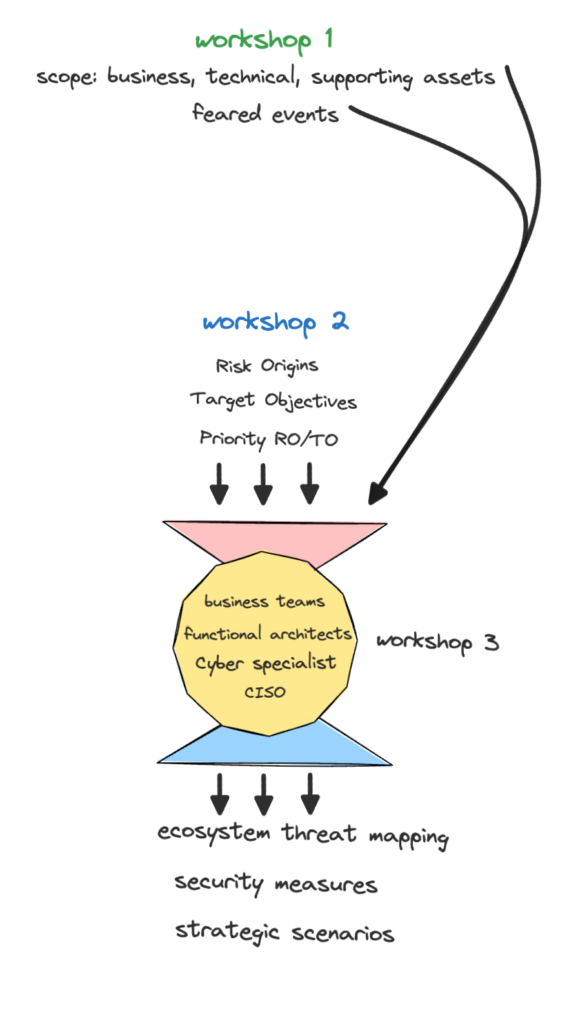

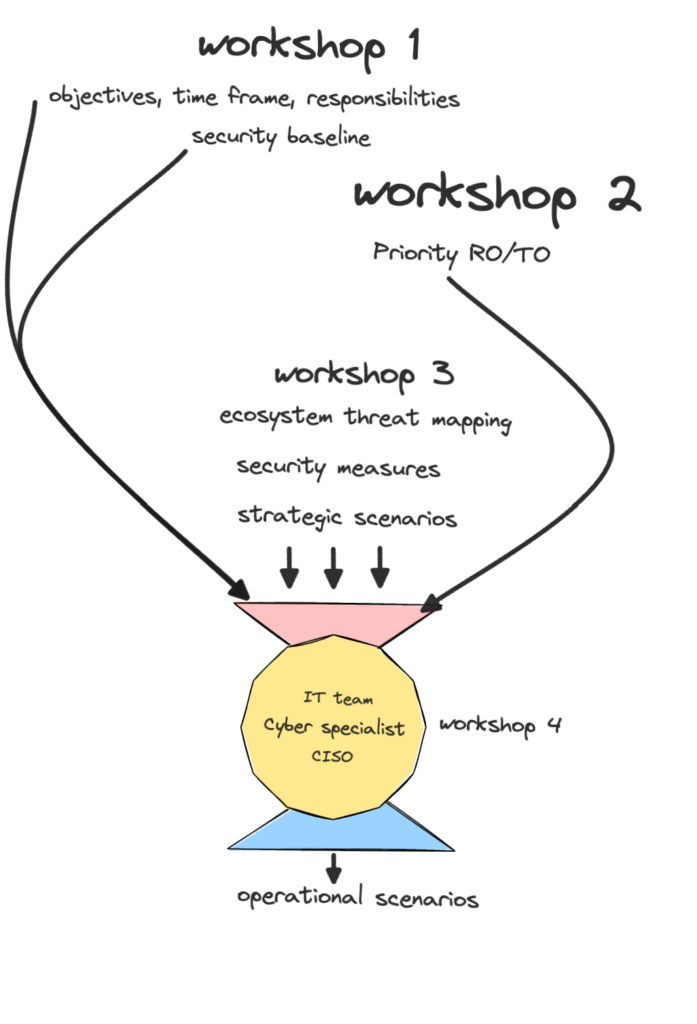

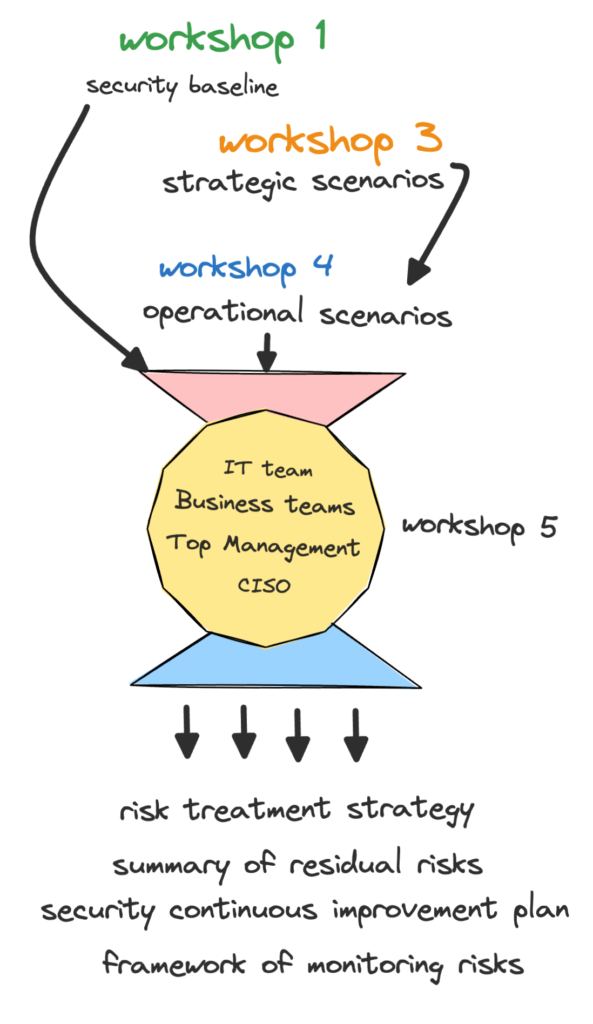

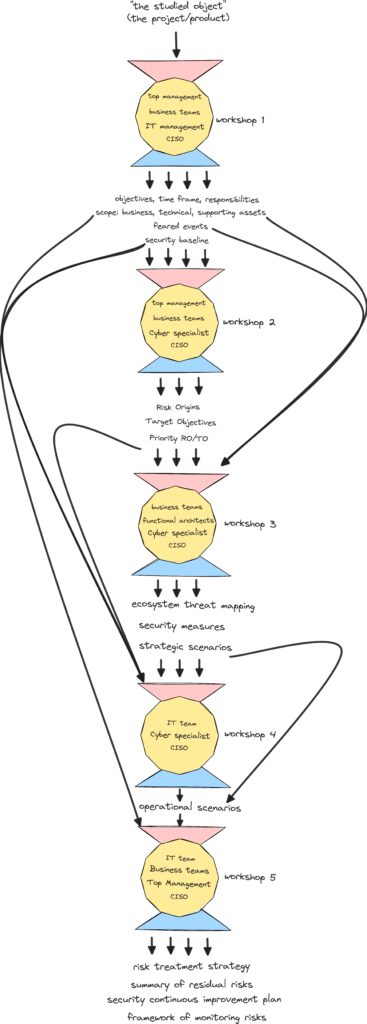

To help with this process EBIOS RM defines 5 workshops: each one with expected inputs, outputs and participants:

Workshop 1:

Workshop 2:

Workshop 3:

Strategic scenario:

- a potential attack with the system as a blackbox: how the attack will happen “from the exterior of the system”

Workshop 4:

Operational/Operative Scenarios – identify and describe potential attack scenarios corresponding to the strategic ones, eventually using tools like: STRIDE, OWASP , MITRE ATT&CK, OCTAVE, Trike, etc.

Workshop 5:

Risk Treatment Strategy Options (ISO27005/27001):

- Avoid (results in a residual risk = 0) – change the context that gives rise to the risk

- Modify (results in a residual risk > 0): add/remove or change security measures in order to decrease/modify the risk (likelihood and/or severity)

- Share or Transfer (results in a residual risk that can be zero or greater : involve an external partner/entity (e.g. insurance)

- Accept (the residual risk stays the same as the original risk)

In Summary:

In Conclusion:

EBIOS RM is a useful tool in the cybersecurity management, aligned with the main cybersecurity tools and frameworks.

There is also enough supporting open access materials (see ANSSI and Club EBIOS ) that help conduct and produce the required artefacts at each step of the process: templates, guides, etc. – which make it a primary candidate for adoption in organisations without an already established cybersecurity risk management practice.